Drones: A threat to some, a living for others. It is very obvious that no matter where you are in the world, drones are becoming more and more common, and are starting to impact the aviation industry globally. To integrate drones into the aviation industry is not something easy to tackle in an when there are so many variables, safety considerations, and perspectives.

Understanding the legal implications of having drones flying around inside and outside controlled airspace is really important for flight safety in general. This applies whether you are a remote drone pilot, an air traffic controller, or a ‘conventional’ aircraft pilot.

Raising awareness about what is and isn’t appropriate as a drone owner might sound like a waste of time to some, due to the open nature of the drone industry.

However, doing our bit to make sure as many people as possible are aware of how their drones impact the aviation industry and airspace around them can only be a good thing!

In this article, we’ll be going over all these main highlights, details and considerations regarding the integration of UAS (Unmanned Aircraft Systems) into the aviation industry. Most of the regulations here will be based on EASA and the UK CAA, but can often be translated to other regulators and regions in the world as well. We’ll cover:

- UAS Types and Classes

- UAS Categories, and Subcategories

- Presenting all the rules into a visual overview

- Change management for drones in our industry

- When to report occurrences, and more importantly: HOW?

- References and links

Ready? Here we go!

Do you like these articles and want to stay up to date with the best & relevant content? Follow Pilots Who Ask Why

Where to Begin?

So where do we even begin? Well let’s break down the basics first and build it up from there. Regulators are still struggling to define what a drone is, and what type of operation any particular drone should be allowed to participate in.

EASA has put a lot of time and effort into providing the industry with a framework that puts it all together in one place. First of all, let’s have a look at the different type of defined drone types:

VLOS vs EVLOS vs BVLOS

Sounds like a mouthful right? These terms simply refer to whether or not you as a remote pilot, can ‘see’ your drone.

VLOS stands for Visual Line of Sight, while BVLOS stands for Beyond Visual Line of Sight, EVLOS stands for Extended Visual Line of Sight.

To quote the UK CAA:

Operating within Visual Line of Sight (VLOS) means that the remote pilot must be able to clearly see the unmanned aircraft and the surrounding airspace at all times while it is airborne. The key requirement of any flight is to avoid collisions and a VLOS operation ensures that the remote pilot is able to monitor the aircraft’s flight path and so manoeuvre it clear of anything that it might collide with. While corrective lenses may be used, the use of binoculars, telescopes, or any other forms of image enhancing devices are not permitted.

This automatically comes with a 400’ height limitation and a 500 m horizontal distance limitations between the drone and the remote pilot, unless you have specific authorisation.

For BVLOS, the UK CAA Defines these as:

Operation of an unmanned aircraft beyond a distance where the remote pilot is able to respond to, or avoid other airspace users, by direct visual means (i.e. the remote pilot’s observation of the unmanned aircraft) is considered to be a BVLOS operation.

One option in the middle is EVLOS. This is where the remote pilot uses other non-technical methods to achieve distances between him/her and the drone that are normally considered beyond line of sight, such as observers or other procedures that are approved and in place.

Now that these 2 (or technically 3) groups are discussed, let’s see how they are further split up within the industry within the categories defined by most regulators globally: OPEN, SPECIFIC, and CERTIFIED.

The Open Category

Most ‘simple’ drones fall into this category. EASA states:

These drones cannot be heavier than 25 kg (which, let’s be honest, is pretty heavy for a drone!), the remote pilot has to make sure that the drone is not flown over assemblies of people and that safe distances are always maintained.

The other hard requirement is that the drone MUST be VLOS (Visual Line of Sight) to be in the open category and cannot be flown further away from the surface than 120 meters (394 feet), and cannot carry any dangerous goods or drop any materials.

The only exception to this rule is when you are flying a drone within 50 meters of an artificial obstacle that is taller than 105 meters.

In this case, the maximum height of the drone can be increased up to 15 meters above the height of the obstacle, but this only applies if the entity responsible for the obstacle requests this specifically. This regulation can be found in UAS.OPEN.010, in the rulebook attached at the bottom of this article!

Within the OPEN category, there are subcategories A1 to A3. These are essentially brackets that are based on the amount of risk involved in the UAS operation.

The higher the risk, the stricter regulations become. It is essential for drone operators to know which bracket they are planning to operate in, and comply with the regulations accordingly! Let’s break them down:

- A1: Fly over people – only UAS that present very low risk to people due to their low weight

- A2: Fly close to people – Only UAS of a particular type and the drone can not be flown closer that 30 meters from uninvolved persons

- A3: Fly far from people – These UAS can only be flown if the area of operation is completely clear of uninvolved persons and may not be flown closer than 150 meters from residential / commercial / industrial areas.

The Specific Category

By default, any drone that does not fit the criteria above, will enter the specific category. The local regulator will need to give authorisation before a flight or before a combination of flights and this needs to be requested beforehand. If you are an operator with the intention of flying drones that do not fit in the previous category, you have to seek specific approval in most regions in the world.

The Certified Category

That leaves us with the last and more rare types of drones. The certified category is for drones that transport people. If the risks for surrounding people is considered larger than what would otherwise be the case in the specific category, the drone will enter the certified category (exceptionally large and heavy drones for instance).

In addition, if the drone carries dangerous goods that are not crash-protected, it will enter the certified category (instead of specific) as well.

So What Drone Classes are There Then?

So, the assignment of how ‘risky’ your operation is allowed to be (subcategory A1 to A3) is dependent on the type of drone you are flying. The OPEN category consists of 5 classes: C0 to C4. C0 includes the smaller drones while C4 covers the drones that are larger in size and payload:

C0

- MTOM (Maximum Take Off Mass) of 250 g

- Max speed in level flight of 19 m/s

- Designed to minimise injury to people during operation

- Only ever powered by electricity

C1

- MTOM of 900 g (or has a maximum impact energy of 80 Joule transmitted to a human head, funny way of defining operational impact huh?)

- Max speed in level flight of 19 m/s

- Must be powered by electricity

- Has to have a geo-awareness function including warnings when breach of airspace is detected with self monitoring as well

- Equipped with lights for the purpose of controlling the UAS and a green nav light at night

- If follow me functions are installed, the maximum range is 50 meters from the remote pilot

C2

- MTOM of 4 kg

- Reliable way of recovering in case of a control or transmittal failure

- Must be powered by electricity

- If tethered: cord has to be less than 50 m and has a strength of over 10 times the weight of the MTOM

C3

- MTOM of less than 25 kg, including payload

- Maximum dimension of less than 3 m

- Has to be compliant with local noise regulations

- Clear warnings of impending power failure

- Still must be powered by electricity

C4

- MOTM of less than 25 kg, including payload

- Not be capable of automatic control modes, except for flight stabilisation assistance

- No longer has to be powered by electricity

As you can see, these are purely based on the drone and its systems, not the operational conditions themselves (like the subcategories A1 to A3). In addition to C0 to C4, we also have C5 and C6, but as these are only relevant to very specific operators, they are not covered in the table that you will see in a minute below.

To give you an idea though, C6 for instance includes drones that can fly up to 50 m/s, which is up to almost 100 kts, which is pretty crazy for a drone!

As the industry develops and matures, the CERTIFIED and SPECIFIC categories will probably also become more branched out, like the open category, more than they are today. We might cover these in a future article.

That is a Lot of Info, How Do I Visualise All of These Rules?

Good question! Due to the complex regulatory nature and the different variables that impact drones, this can be a bit of a minefield unfortunately.

To give you an accurate overview of the confirmed future structure EASA will adopt, please see the table below to get a birds-eye view on what the situation will look like in the future, which applies to the OPEN category.

The reason this is only featuring the OPEN category, is because it’s the biggest bracket in today’s industry, and is the only category that can be tied to relatively straight forward rule structures (I agree, it’s a subjective term).

As the other two have such bespoke components and requirements they are hard to put in a table like this.

If you’re an even bigger aviation geek than this article can satisfy, the EASA and CAA publications that cover the info portrayed in the table above, is accessible at the bottom of this article.

Drone Safety Management

Promoting a safe, but at the same time, open drone industry can be a slippery slope. Usually extra steps in improving safety, or adding ‘layers of swiss cheese’ for the aviators here, results in less accessibility. This is mainly due to the fact that these steps usually make it harder to comply with the regulation, wherever you might be.

So let’s have a look at what regulators should be focussing on to incorporate drones into the industry while at the same time not making it impossible to flourish as an industry.

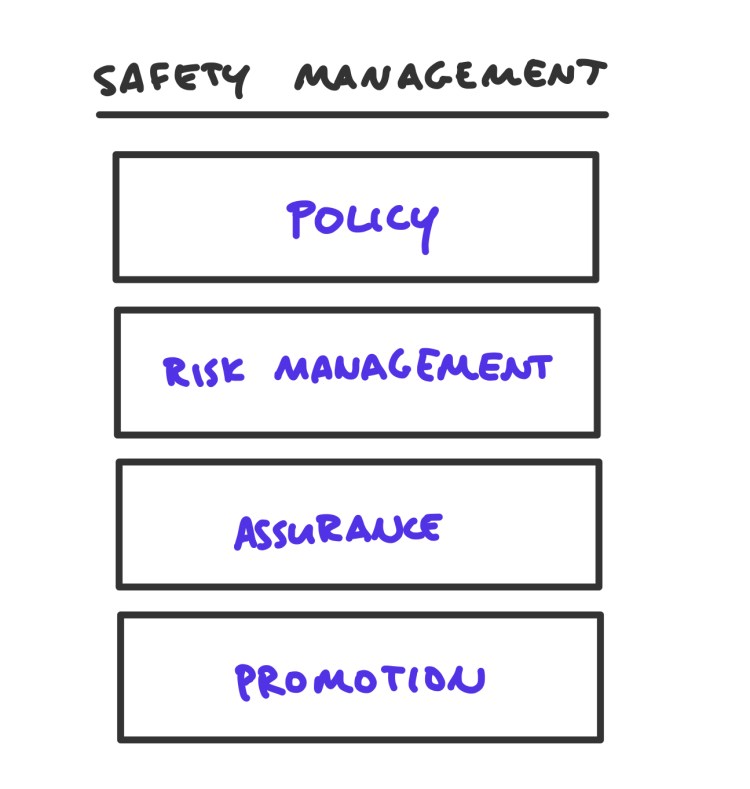

For the change management experts in the audience this is going to be a little basic, but let’s lay down what the road ahead should look like from an industry’s point of view. Let’s zoom in at the widely discussed and defined four pillars of safety management:

You might recognise these if you are involved in a company that values an open safety culture as well. The higher the quality of each pillar, the more streamlined and effective the integration of drones will be. These apply to all the parties that make up the industry, including:

- The drone manufacturers

- The maintenance organisations

- Air Traffic Control

- The drone operators and remote pilots

- Airports

- Training organisations

- Local Regulators

Let’s start with:

Policy

The people who define drone rules and regulations should first of all be empowered to do so. They need to have access to data, evidence, and should be able to measure the effects of their policies. The three main questions here are:

- Are the drone policies widely available and is the industry engaged and supportive?

- Does the drone industry appreciate the effects and importance of safety improvements?

- Is it possible to have 2-way communications (industry vs regulator) in place to process feedback?

Risk Management

High level decisions should be made using risk-based analysis. Having a drone industry where there are so many safety barriers in place that the industry itself is no longer feasible, vs having an industry that is so open that accidents happen on a weekly basis: there is a middle ground somewhere. The question is of course: where? The three main questions here are:

- Is it easy and encouraged to submit drone occurrence reports? If there are barriers, what are they and how can they be removed?

- Are the drone occurrence reports actually used for future change and improvements?

- Are there an adequate amount of resources allocated to making sure the drone risk controls are implemented properly?

Assurance

The act of making sure that the changes and improvement are actually being utilised. The three main questions here are:

- Are drone risk controls actually implemented, and actually effective?

- How often do reviews take place?

- Are drone safety objectives actually reached over a period of time?

Promotion

And finally, the safety improvements need to be actively communicated, promoted, and encouraged. If this doesn’t happen, we can safely assume that trying to change an industry in such a massive way, as we see with the drone implementation into the aviation industry, will be a massive hurdle!

- Are the drone policies applied in a large enough area?

- Is the industry still engaged with changes over time?

- Is enough awareness being raised by the ones in charge?

All of these will impact the next 10 years massively. And only if all four categories get implemented properly, will the industry seamlessly adopt drones properly.

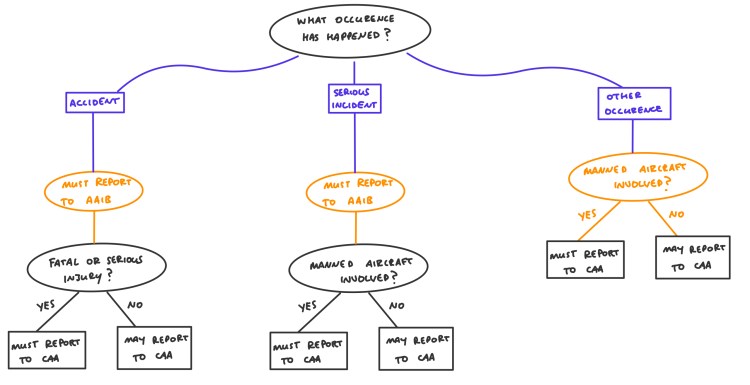

To finish drone safety, let’s give you some reference now to know whether or not an occurrence should be reported or not, as this can be confusing at times.

UAS Occurrence Reporting

Knowing what occurences involving drones to report is important as well. As most of us know already, occurence reporting systems do not exist to assign blame or liability.

While reporting incidents is improving year by year, having so many new people enter the aviation industry because of drones, calls for taking some time to re-emphasise how important reporting is to learn from mistakes and improve overall safety.

Not sure when to report within the UK (and most of Europe)? Here is a flowchart that should help. Keep in mind that if you’re not sure, it’s always best to report anyway.

To report to the AAIB, use this link.

To report to the UK CAA, use this link.

Conclusion

There we have it, drones entering our beloved aviation industry. Only with discussion, open mindedness, debate and proper policies will the next few years be successful. For any questions, comments or ideas, please leave a message below, or feel free to contact me personally (contact details at the top right). For now, Merry Christmas and see you in 2022!

References

Please find all the relevant sources for UAS regulations and limitations here in Europe and the UK, feel free to download them yourself for reference in the future. The last few links are handy websites and resources for remote pilots.

Links

AIRMAP – Free Worldwide Airspace Management Software for Drones

2 Comments

David D Wallace · December 19, 2021 at 3:26 PM

Thanks for the information sir. Very helpful.

Jop Dingemans - pilotswhoaskwhy.com · December 19, 2021 at 3:42 PM

My pleasure David, thank you for the feedback!